By Kunchok Dolma Yaklha, Special Appointee for Human Rights

Last week the U.S. State Department issued an updated travel advisory for China, warning American citizens about the “arbitrary enforcement of local laws” there, including the “exit bans” which bar individuals from leaving the country.

Beijing’s move comes as a retaliation against the recent arrest of Chinese tech giant Huawei’s CFO Meng Wanzhou, the daughter of the company’s founder Ren Zhenfei.

Arrest of Huawei’s executive in Canada

Meng was arrested in Vancouver, Canada – where she was on a layover between Hong Kong and Mexico – at the request of American counterparts on December 1, 2018. She is now facing possible extradition to the U.S. to stand trial on allegations over helping banks with certain business activities that violated American sanctions against Iran.

Huawei, the world’s largest telecom equipment supplier, as a company is under intense scrutiny because of its suspected ties with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

Members of the Five Eyes intelligence-sharing alliance—composed of Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the U.K., and the U.S.—have deemed Huawei as a serious national security threat on the grounds that it could be operating as a spy for the CCP.

China retaliates against Meng’s arrest

Angered over Meng’s arrest, 13 Canadians were detained in China in the last month according to Global Affairs Canada.

However, the detention of only three Canadians: Michael Kovrig, a former Canadian diplomat working for the International Crisis Group; Michael Spavor, a businessman focusing on promoting tourism and investment in North Korea; and Sarah McIver, an English teacher who returned to Canada after being released, are known to the public.

Former diplomat Michael Kovrig (left) and entrepreneur Michael Spavor (right)

are two Canadians currently detained in China. Photo: AP

Kovrig and Spavor continue to be detained on suspicion of “engaging in activities endangering the national security” of China. Little information about the two detainees in China have been released apart from the fact that they were granted one consular access.

Meanwhile, Meng is out on bail and staying in one of her luxury homes in Vancouver.

Tibetans’ first-hand experience of China’s arbitrary enforcement of local laws

For years, Tibetans have been telling the international community about the Chinese government’s arbitrary and selective enforcement of local laws to suppress any activity it does not like.

China has a deeply flawed justice system with a conviction rate of 99.9% and politically charged cases are particularly bound to have guilty verdicts. It is not uncommon for prisoners to be denied access to a lawyer or information about the alleged crime and be subjected to prolonged interrogation, torture and other ill-treatment.

Tibetans have a first-hand experience of China’s lack of respect for the rule of law.

Tashi Wangchuk and the circumstances surrounding his case is the latest visible example. The Tibetan language rights activist was handed 5 years in prison in May 2018 for “inciting separatism” after he appeared in a New York Times video documentary expressing concerns about Tibetan children not being able to speak their native language.

Tashi Wangchuk at a traditional horse festival in the Tibetan area of Yushu, Qinghai

Province, China, in 2015. Tashi was sentenced to 5 years in prison last year after he

spoke to the New York Times about Tibetan language education. Photo: NYT

Article 4 of the Chinese constitution protects the rights of minority nationalities “to use and develop their own spoken and written languages.” Tashi’s campaign for Tibetan language education in schools was in accordance with Chinese law, yet he finds himself behind bars.

Tashi’s family were not informed about his arrest until almost two months after—in contravention of Chinese criminal law which requires family members of a detainee to be informed within 24 hours of arrest.

Representatives from Canada, Germany, the European Union, the U.K., and the U.S., were all denied entry to Tashi’s trial proceedings at the Yushu Intermediate People’s Court.

Tenzin Delek Rinpoche, a prominent Tibetan religious leader, died in Chinese custody on July 13, 2015, after having completed 13 years of his life imprisonment sentence on charges of “terrorism and inciting separatism.”

The Chinese government claimed Rinpoche died of a heart attack, however, his niece Nyima Lhamo, who later escaped to India, met with political leaders and international human rights organizations and revealed that Rinpoche had in fact been poisoned to death.

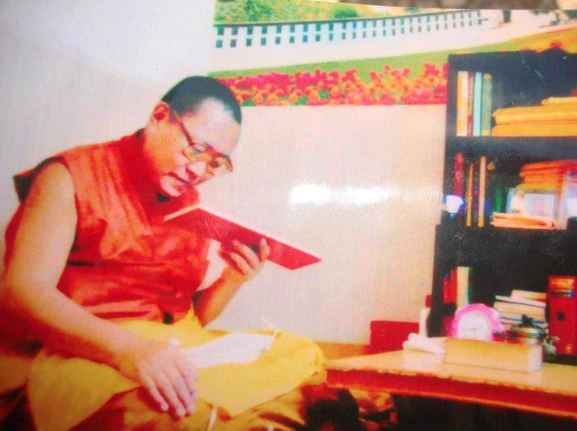

Reportedly, Chinese officials gave this photo of Tenzin Delek Rinpoche to visiting relatives,

claiming to show him in prison. Rinpoche died in a Chinese prison in 2015 under suspicious

circumstances. Photo: Woeser

Human Rights Watch said the case was plagued with irregularities and lacked any credible evidence against Rinpoche. “[M]any reasons remain for questioning [the court’s] findings…The trial was procedurally flawed, the court was neither independent nor impartial.” Citing national security reasons, Chinese authorities refused to release any evidence used at trial.

Rinpoche’s case was widely viewed as politically motivated and an attempt to silence him, given his growing popularity among the locals as a defender of rights of Tibetans.

Vague laws giving Chinese authorities broad discretionary powers

Vague and overbroad language in a series of national-security related laws introduced in 2014 empower the Chinese government with far-reaching powers to criminalize activities it seems fit.

The UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD) has expressed concerns over China’s use of “broad definition of terrorism and vague references to extremism and unclear definition of separatism” potentially being used to “criminalize peaceful civic and religious expression and facilitating profiling” of Tibetans and other minorities nationals in the country.

In February 2018, China’s Public Security Bureau of the so-called Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) issued a notice officially listing a series of Tibetan social practices, such as language preservation and environmental protection, as forms of organized crime. Any close ties to His Holiness the Dalai Lama referred to as the “Dalai clique” in the circular, or support for the Middle Way approach (which seeks genuine autonomy for Tibetans under the framework of the Chinese constitution) are also deemed illegal.

The absurd local laws are supported by intensified state surveillance as noted by the U.S. State Department’s recent travel advisory for China. “Extra security measures, such as security checks and increased levels of police presence, are common” in the so-called Tibet Autonomous Region and “[a]uthorities may impose curfews and travel restrictions on short notice,” states the advisory.

For too long, the world was under the impression that only vulnerable communities like Tibetans were subject to China’s gross injustice.

We now know whether it’s Tibetans, Canadians or Americans, no one is safe from China’s arbitrary enforcement of local laws.

Better late than never.