The Citizenlab, 30 January 2018 Read original story here

Key Findings

- This report analyzes an extensive phishing operation with targets in the Tibetan community. Our analysis indicates other possible targets among ethnic minorities, social movements, a media group, and government agencies in South and Southeast Asia.

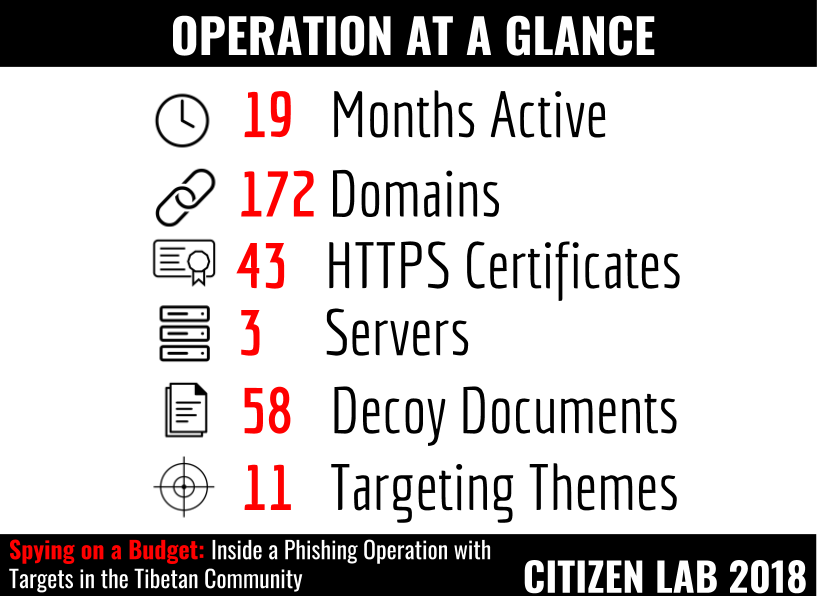

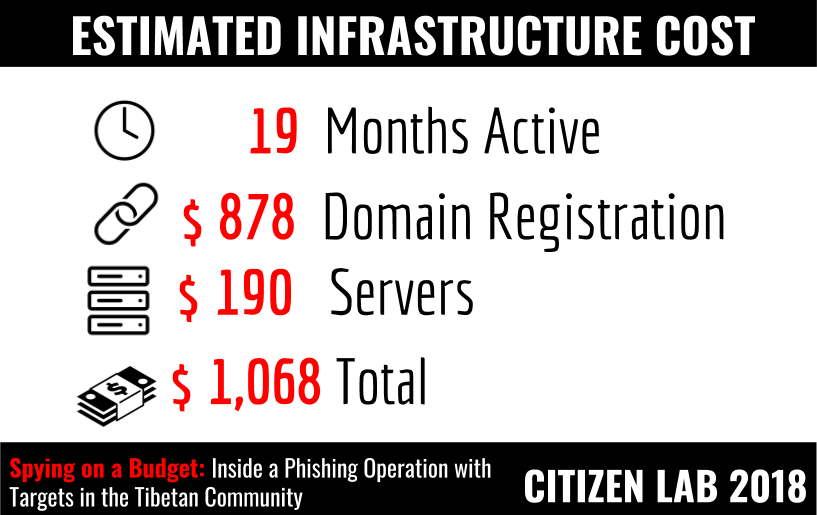

- The operation was simplistic and inexpensive, yet achieved some successes. We estimate the infrastructure used in the operation cost slightly over 1,000 USD to setup and required only basic system administration and web development skills to maintain.

- The operation illustrates that the continued low adoption rates for digital security features, such as two factor authentication, contribute to the low bar to entry for digital espionage through basic phishing.

Summary

Civil society groups around the world are persistently targeted by digital espionage operations designed to collect sensitive information on their communications and activities. Activists, humanitarians, and journalists often work in distributed groups and rely on the same consumer platforms as average users. Phishing is a technically simple and relatively low cost tactic to gain access to accounts on these platforms and compromise individuals and organizations. Recent research has documented phishing operations targeting civil society groups across Asia, South America, and the Middle East.

In this report, we provide an in-depth view into a phishing operation that ran for 19 months, and which targeted the Tibetan community, and potentially other groups including ethnic minorities, social movements related to China, a media group, and government agencies in South and Southeast Asia. The targeting themes have general geographic and contextual commonalities, but it is unclear who the sponsor of the operation is and how information collected by it may be used.

The operation used a range of phishing tactics including pages impersonating popular email provider logins, custom webmail login pages to target specific providers and organizations, and malicious OAuth applications for harvesting Google credentials.

The Tibetan community has been persistently targeted by digital espionage operations for over a decade. Historically, malware sent as email attachments was the most common threat Tibetan groups experienced. Recently, we have observed an increase in phishing operations targeting the community suggesting a possible shift in adversary tactics. This latest operation is another example of this trend.

The phishing tactics used in the operation could have been blunted if targets used security features like two factor authentication, which requires a second ‘factor’ to access an account.[1] Unfortunately, two factor authentication is not enabled by default on most popular platforms, and there are a number of hurdles to ensuring widespread adoption among civil society groups such as lack of awareness, potential usability issues, and the general challenge of shifting user behaviour across a community. Adoption rates for two factor authentication across user populations are very limited. For example, according to a recent presentation by a Google employee less than 10% of Gmail users have enabled two factor authentication.

As long as two factor adoption rates remain low, the entry cost for engaging in credential theft will be low as well. Major platforms can help shift the balance by undertaking efforts to encourage or move their users towards widespread use of two factor authentication.

This report proceeds in three parts:

Part 1: Uncovering a Persistent Phishing Operation

This section outlines how we first became aware of the phishing activity and our subsequent infrastructure tracking and analysis that revealed the wider operation.

Part 2: Targeting

This section describes our analysis of the targets and tactics of the operation, including phishing that targeted Tibetan groups and decoy documents that show potential targets beyond the Tibetan community.

Part 3: Discussion and Conclusion

This section discusses the implications of our analysis.

Part 1: Uncovering a Persistent Phishing Operation

This section outlines how we first became aware of the phishing activity and subsequent infrastructure tracking and analysis that led to discovery of the wider operation.

Mimics and Decoys

We first encountered the phishing operation in December 2016 when a Tibetan activist received an email that appeared to come from a member of the Central Tibetan Administration (CTA, the Tibetan Government in Exile). The message was designed to trick the activist into visiting a fake Google login page and entering their credentials. We observed similar tactics in a 2015 phishing campaign targeting Tibetan activists and journalists.

A Representative Phishing Email

The email, which is representative of the general social engineering tactics used in the operation, included several elements designed to increase the credibility of the message and subsequently disguise from the target that their credentials had been phished.

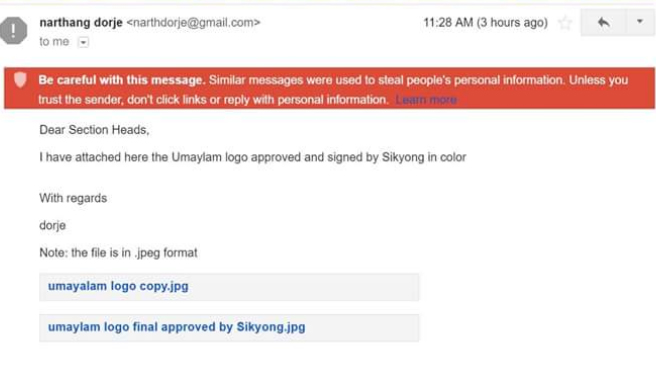

The sender appeared to work for the Narthang Press, a division of the CTA responsible for printing official materials. The email included logos of the Umaylam website[2] and a message that claimed the files had been approved by the Tibetan Prime Minister (referred to as the Sikyong in Tibetan). In the screenshot of the email shown in Figure 1, Gmail has flagged the email as suspicious giving the recipient an indication that something is not right.

The Phishing Page

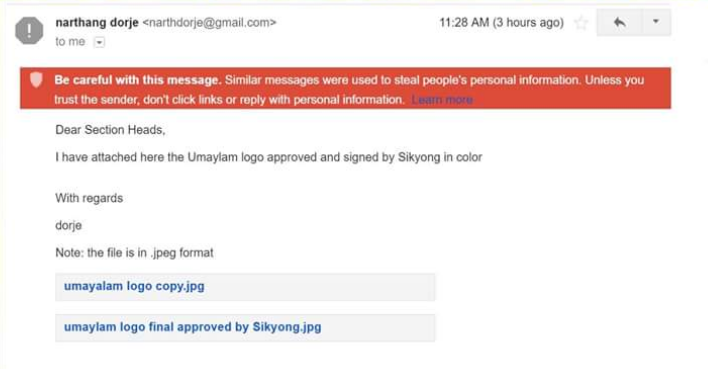

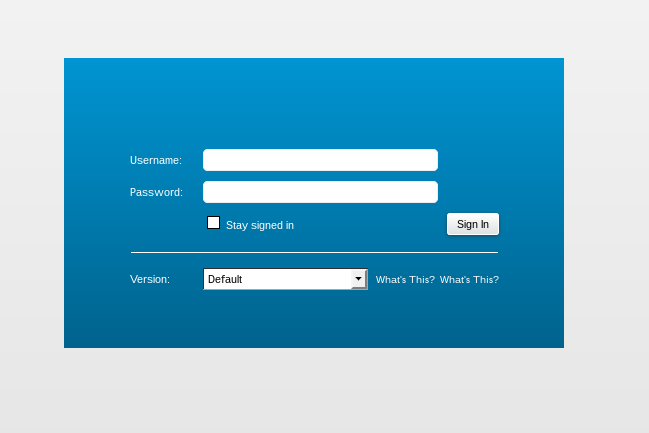

While the email appeared to send attachments, the files were actually links to a domain that was made to look like a Google Drive domain: drive-google[.]ml. Clicking on the link sends the user to what appears to be a Google login page (See Figure 2).

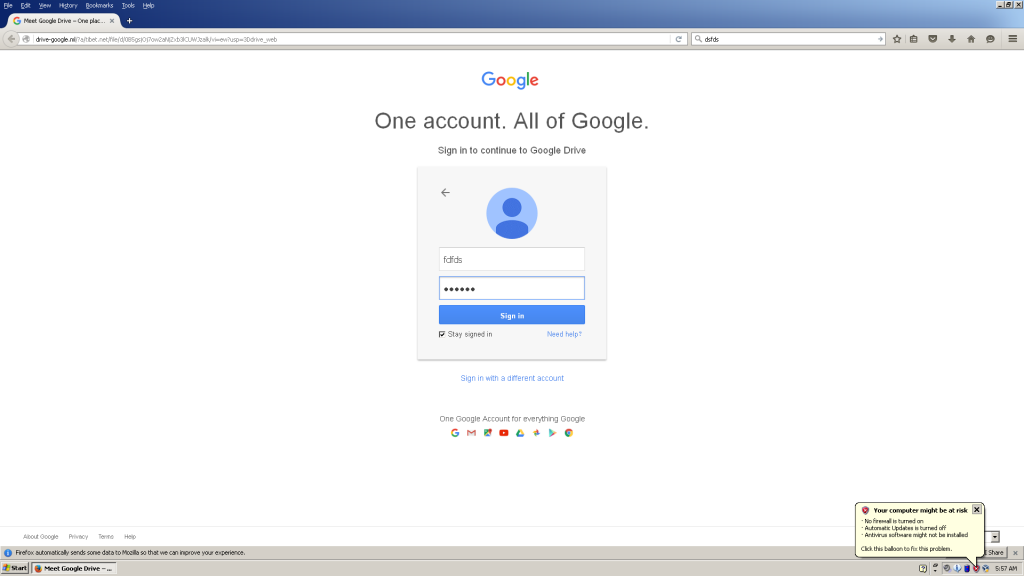

While at first glance the page may look legitimate, it is actually copying an outdated version of the authentic Google login page. The phishing page includes both username and password prompts on the same page. Google has been using a two-prompt process for authentication since May 2015 (see Figure 3).

The Decoy Document

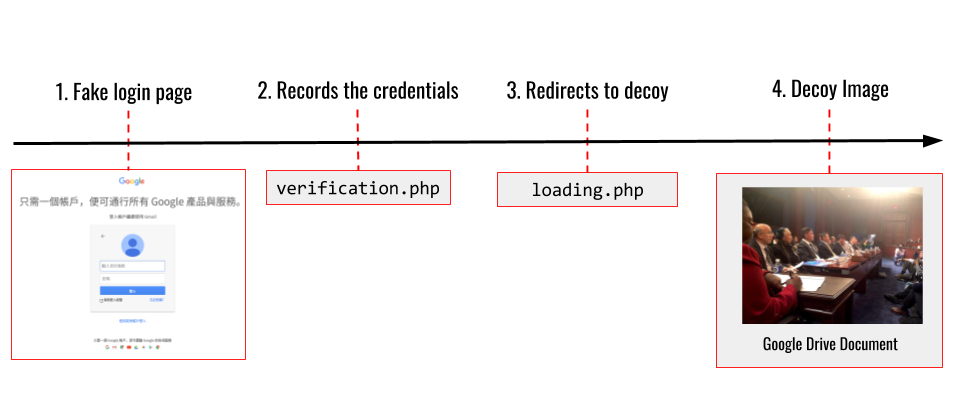

If the user enters credentials into this page, the form sends their login and password to the local page verification.php, which redirects to the page loading.php. The loading.php page finally redirects the user to decoy content on Google Drive, in this case the Umaylam logo described in the email. This decoy content supports the deception by providing a credible looking file legitimately hosted by Google (See Figure 4).

Revealing a Wider Operation

Following the first phishing email we received, we collected further samples sent to staff members of two Tibetan human rights groups. We then examined passive DNS data and domain registration information from phishing pages that were linked in the emails and found related domains and server infrastructure. We then used these indicators to search email accounts of individuals and groups in the Tibetan community. Through this search, we identified an additional 24 phishing emails sent between March 21 2016 and February 21 2017 (We explore the targeting of the Tibetan community in depth in Part 2: Targeting).

Further analysis of the domains and servers used to host phishing pages and decoy documents revealed that the infrastructure was active as early as January 11, 2016. However we do not have phishing emails from this earlier period. The operation used a range of phishing tactics including pages impersonating popular email provider logins (e.g., Gmail, Yahoo, Microsoft Live, etc.), custom webmail login pages to target smaller providers and specific organizations, and malicious OAuth apps for harvesting Google credentials.

Cost and Labor of Phishing

The operation was prolific and used some clever social engineering tricks, but was technically simplistic and inexpensive to setup and maintain. Based on the services used in the operation, we estimate that the infrastructure could be run for a little over 1,000 USD.[3]

The greater cost associated with the operation is human effort. Running the infrastructure and phishing campaigns would require only basic system administration and web development skills. However, maintaining and administering the operation is a time commitment. Tracking the operators’ activities provides a look into this process from setting up domains, preparing phishing emails and decoy documents to compromising targets and harvesting information. Based on our analysis of the workflow there is little evidence of any automation — suggesting that the process was likely a largely manual effort.

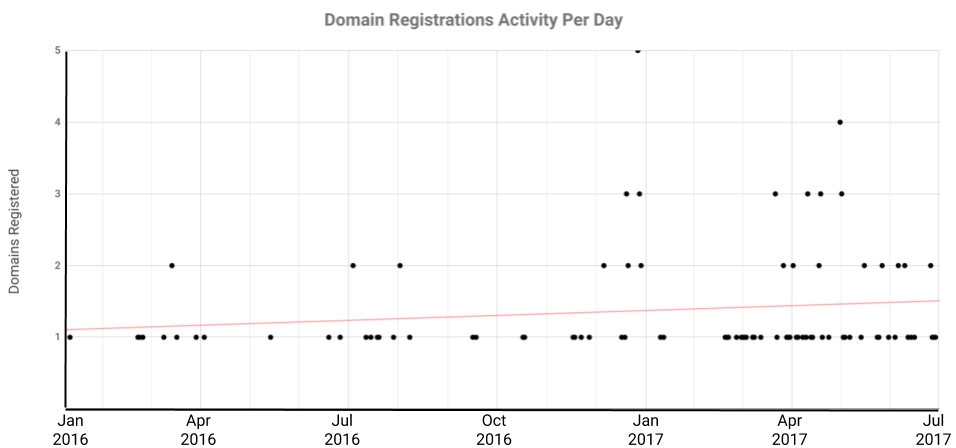

Registering the 172 domains used in the operation took up the bulk of infrastructure setup. The operators never reused domains and registered them in batches. Reviewing available domain registration shows that in active periods between one to five domains were registered a day with an average of 1.3 domains registered per day (see Figure 7). The most active day was December 27 2016 when the operators registered five domains. The operators often reused registrant information (i.e., names, phone numbers, and emails) to register the domains. In total, 39 unique identity indicators were used to register the 172 domains (17 names, 12 phone numbers, 10 emails). Registration information often included misspellings (e.g., London” as ‘“lodon”) and filler text, such as using a registrant street address of “chan youshd hjsksasddsdfs dgfs”. The cycle of registrations, reuse of registrant information, and misspelled fields suggest this process was done manually.

Based on the phishing emails collected from Tibetan groups it appears that, once registered, the operators quickly used new domains for phishing pages. The majority of emails were sent on the same day, or a day after a new phishing domain was created (the average time between domain registration and the domain being used in a phishing email was 1.2 days).

The majority of decoy content we collected (96%) was hosted on Google Drive. Different Gmail addresses were used to upload each decoy file. In some cases we found mismatches between the messages in the phishing emails and the decoy content suggesting the operators had made an error.

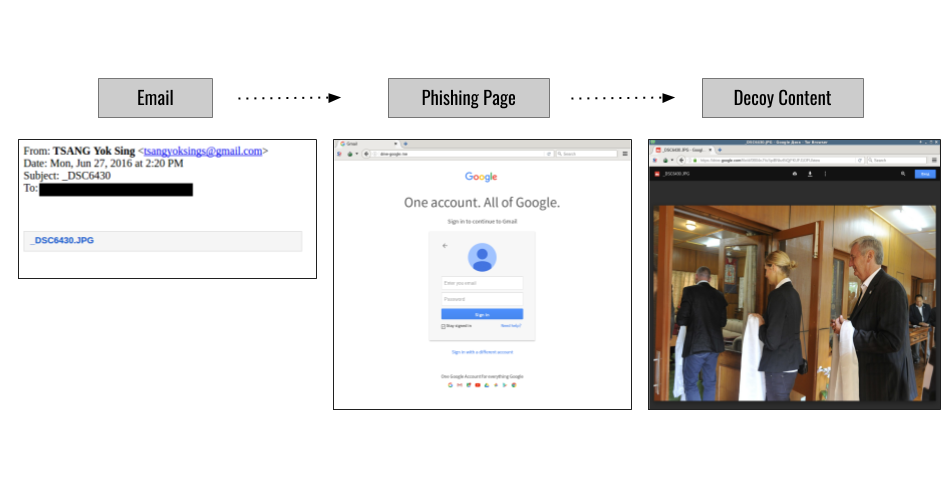

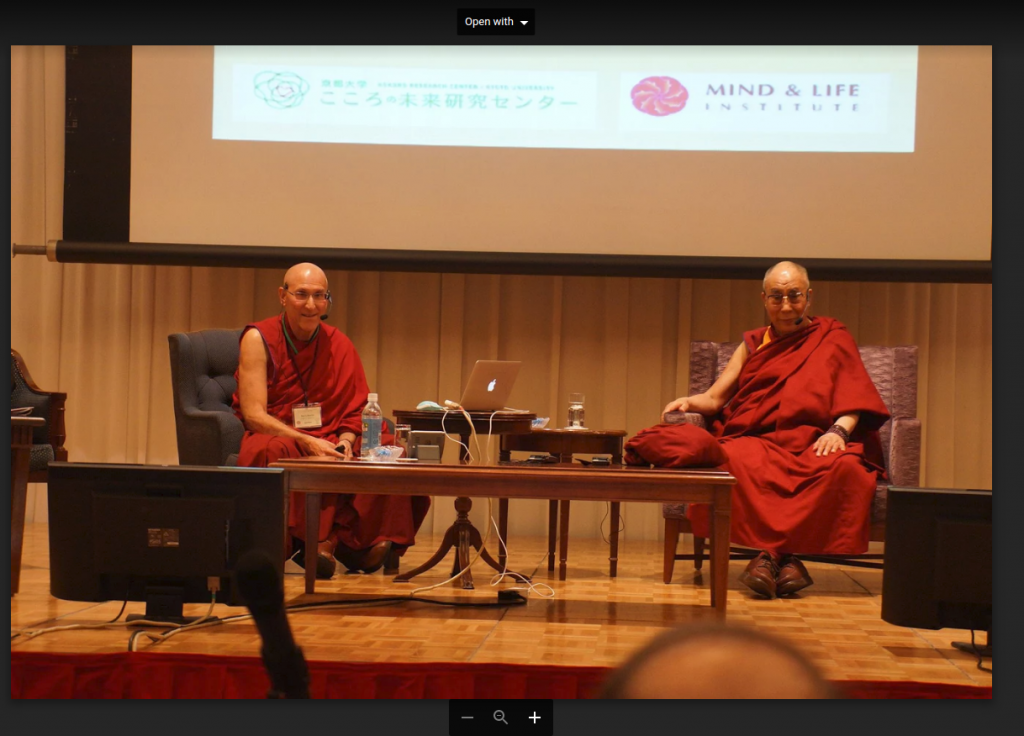

In one example a phishing email sent to a Tibetan activist appeared to come from Jasper Tsang Yok-sing who was the second president of the Legislative Council of Hong Kong and the founding chairman of the largest pro-Beijing political party in Hong Kong. The phishing email was sent from tsangyoksings@gmail.com, which closely resembles the actual email of Tsang (tsangyoksing@gmail.com) with the addition of an extra “s”. The email content was sparse referencing only an image file (DSC_6430) with a link to a Google login phishing page. If credentials are entered the user is redirected to an image with the same filename on Google Drive that shows delegates at a Tibetan meeting (see Figure 8).

The operators clearly put effort into creating a believable spoof of Tsang’s email and the message, while terse, matches the decoy content that is served. However there is no clear contextual link between the email sender and content. Moreover, an email from a pro-Beijing Hong Kong politician is unlikely to resonate with Tibetan activists. It is possible that the spoofed email may have been used in other targeting and was inadvertently used in this attempt.

The final task for the operators is monitoring for successful compromises and collecting information from the accounts. We have evidence of at least two compromised accounts that show the operators using contact information likely collected from the accounts to send out more phishing emails. We suspect the operators had further success based on decoy documents we collected that appear to be private files, which may have been collected from compromised accounts.

Infrastructure Analysis

The operators demonstrated poor operational security using a small pool of emails and phone numbers to register domains and relying on a limited set of servers that were used one at a time, which helped us map and track their activities.

We conducted daily probing of the infrastructure from February 23 to July 5, 2017 when the infrastructure and campaign became inactive. Tracking consisted of daily visits to the IPs, documenting changes in WHOIS and domain information, and saving copies of identified phishing pages and decoy documents.

A misconfiguration of one of the servers used by the operators gave us further visibility into the domains. The operators pointed their web server HTTPS root to the correct subdirectories while leaving the HTTP root pointed to the default top level directory. This mistake allowed us to track any new domains that pointed to the server over the month of February 2017.

We were able to download the decoy documents that would be returned if users had entered credentials into the phishing pages (the majority of these decoy documents were hosted on Google Drive). Collection of decoy documents was done without actually providing credentials as the phishing pages returned decoys when accessing URL endpoints such as /verification.php or /loading.php.

On July 5, 2017, the server infrastructure used by the operators was shut down. All content was removed from the web server and we did not observe any further domain registrations by the WHOIS registrants we were tracking, nor any evidence that the operators moved to new infrastructure.

Targeted Email Services

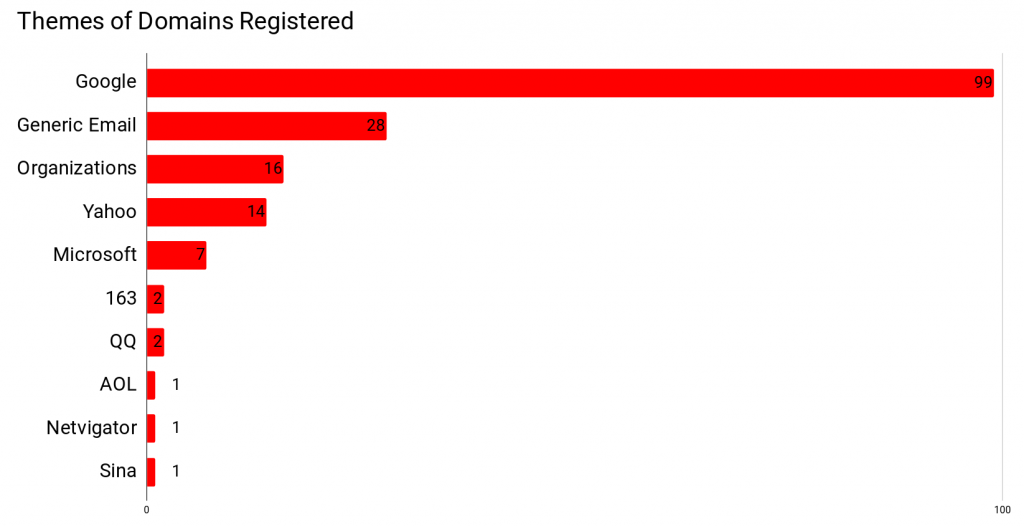

The majority of domains registered during the operation had names that mimicked popular web services, predominantly those offered by Google (e.g., account-gooogle[.]info). Other domains used generic names including the word “email” or “mailbox” (e.g., accounts-mailbox[.]space), or targeted mail services of specific organizations (e.g., dalailama[.]space). Figure 9 shows an overview of domain themes.

Server Infrastructure

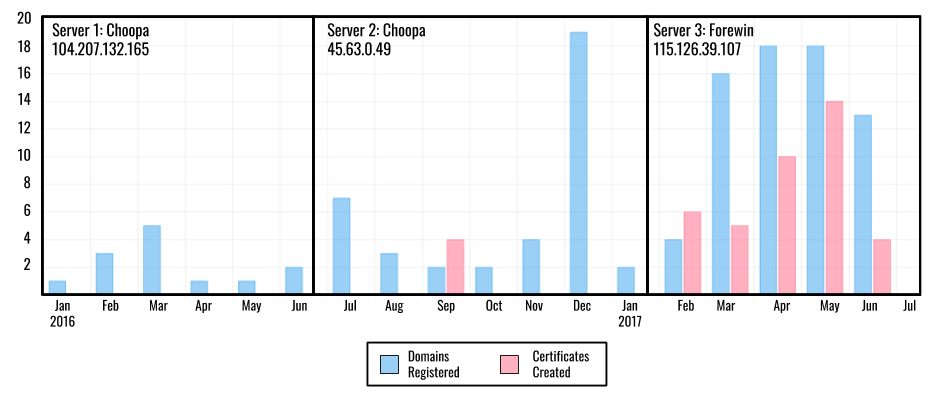

In contrast with the high number of domains, only three servers were used in the operation (see Table 1). Through Passive DNS records we confirmed the operators first setup infrastructure on the hosting provider Choopa. Based on historical information provided by Censys(a database of networks and hosts in the IPv4 address space), we found that on June 27, 2016 the operators moved to a different server on the same provider running Ubuntu. In February 2017, the operators moved to a new hosting provider, Forewin, and switched the server operating system to Windows 7. The change from Linux to Windows may reflect a change in the team administering the infrastructure to an individual more familiar with Windows administration than Linux.

| IP Address | Start Date | End Date | OS | Provider | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

104.207.132[.]165 |

Between December 2015 and February 2016 | June 20, 2016 | Ubuntu | Choopa | USA |

45.63.0[.]49 |

June 27 2016 | February 7 2017 | Ubuntu | Choopa | USA |

115.126.39[.]107 |

February 23 2017 | July 5 2017 | Windows 7 SP1 | Forewin | Hong Kong |

Table 1: List of IP addresses used in the operation

The shift to a new server and operating system in February 2017 is also correlated with an increase in number of registered domains[4]and HTTPS certificates created (See Figure 10). During this period we observed decoy documents and domain names that suggest targeting beyond the Tibetan community (See Part 2: Targeting for details).

Valid HTTPS Certificates

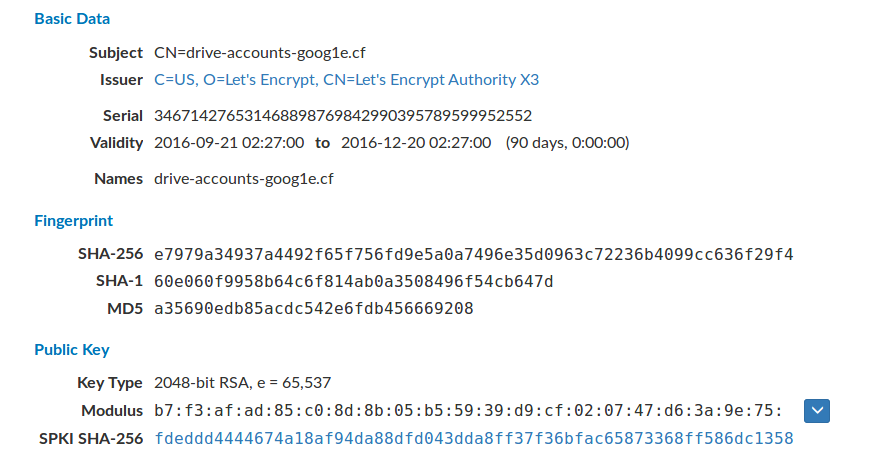

We identified a total of 43 different valid HTTPS certificates created by the operators. Four of these certificates were created in September 2016 using Let’s Encrypt, a free, automated, and open certificate authority. Thirty-nine certificates were made using Comodo. Our analysis found that for the HTTPS certificates made with Comodo the operators leveraged a bug on a platform from hosting provider UK2, which allowed free registration of certificates. Figure 11 shows certificate details for the domain drive-accounts-goog1e[.]cfwhich hosted a phishing page used in the campaign and had a valid Let’s Encrypt certificate installed on its server from September 21 to December 20, 2016.

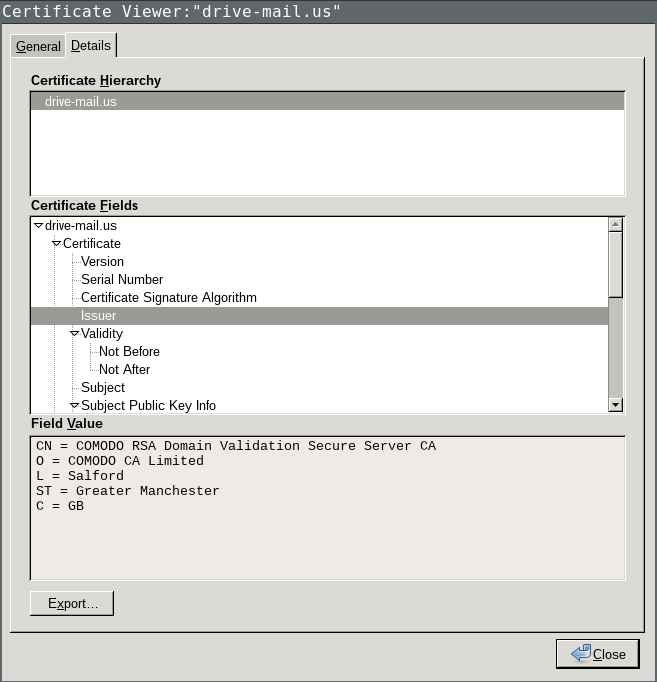

In February 2017, the operators began to use valid Comodo HTTPS certificates for the majority of domains (see an example in Figure 12). The change to Comodo certificates is correlated with the infrastructure moving from an Ubuntu server to a Windows 7 server (115.126.39[.]107) in February 2017. The operators may have moved from Let’s Encrypt to Comodo, because Certbot (the most common tool used to deploy Let’s Encrypt certificates) is not available on Windows systems.

Exploiting a Certificate Registration Bug

Analysis of the domains shows that the operators leveraged a bug in hosting provider, UK2 that enabled them to generate free certificates that were only intended for genuine UK2 customers.

UK2 has given free certificates to their customers since 2007, which are provided by Comodo. However, a bug in their platform could be exploited to get free certificates without being a UK2 customer. The bug relied on how the UK2 platform confirms that users are customers. The platform runs user verification by checking that the domain provided by the user redirects to an IP in UK2 range. As domain owners have full control of IP resolution, it is trivial to configure the domain to resolve to a UK2 IP, obtain a free certificate, and then change the IP resolution to the real IP used by the domain. This bug has been documented on Chinese IT blogs since at least June 2015 (e.g., 1, 2).

We found that five domains used by the operators with Comodo certificates temporarily resolved to IPs in the UK2 address space, but we did not observe UK2 servers being used to host phishing pages. We confirmed the bug and disclosed it to UK2 in October 2017, but did not receive acknowledgement of our report from the company. In November 2017, the public URL allowing users to request certificates was updated to only allow requests from UK2 authenticated users, fixing this issue.

Phishing Tactics

The operation used a range of phishing tactics including pages impersonating popular email provider logins (e.g., Gmail, Yahoo, Microsoft Live, etc), custom webmail login pages to target specific providers and organizations, and malicious OAuth applications for harvesting Google credentials.

Phishing Kits

The most common tactic used in the operation was phishing pages that impersonated popular email providers including: Gmail (English and Chinese login pages), Yahoo (English and Chinese login pages), Microsoft Live, Microsoft Outlook, and AOL. The majority of phishing pages targeted Google services.

Our tests on the fake Google login pages confirmed that when credentials are entered, the form sends username and password information to the local page verification.php, which redirects to the page loading.php. This last page finally redirects the user to a Google Drive hosted image corresponding to the topic in the email. Figure 13 shows examples of the phishing kit redirection process.

Other fake login pages had a different process. Similar to the fake Google login pages, fake Yahoo login pages used an outdated one-page prompt process. Since 2016, Yahoo switched to two-page prompt authentication (see Figure 14). However, if users enter credentials into this page no request was made to the loading.php page. Instead from the request to verification.php the user is redirected to the real Yahoo login page.

The operators also created domains and custom login pages to mimic specific organizations. For example, Table 2 shows a series of domains the operators registered that are designed to look like the official website for His Holiness the Dalai Lama (dalailama.com).

| Domain | Registration date | Registrar |

|---|---|---|

| webmail-dalailama[.]space | 2017-05-27 | GoDaddy |

| webmail-dalailama[.]com | 2017-04-06 | GoDaddy |

| dalailama[.]space | 2017-04-02 | Go Daddy |

Table 2: Registration information for fake domains mimicking the official website of His Holiness the Dalai Lama

These domains hosted a fake Zimbra mail login that copies the webmail login page from the real website (https://webmail.dalailama.com/). Zimbra is an e-mail server suite that is typically self-hosted.

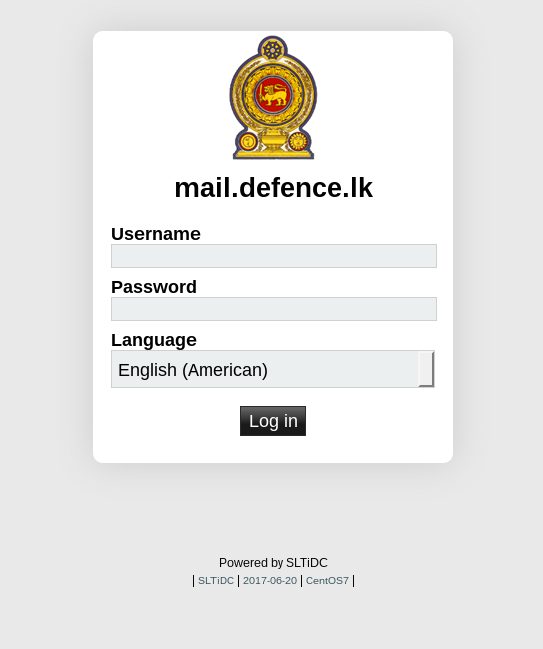

Other customized login pages included mimics of the webmail page for Epoch Times (a multilingual media organization started by Chinese-American Falun Gong supporters), and military and government agencies including the Sri Lanka Defence Department (see Figure 16) and the government of Punjab in Pakistan (we explore these targeting themes in detail in Part 2: Targeting).

OAuth Phishing

Open Authentication (OAuth) is a protocol designed for access delegation and has become a popular way for major platforms (e.g., Facebook, Google, Twitter, etc.) to permit sharing of account information with third party applications.

Malicious OAuth applications have been used in phishing attacks both in targeted operations and generic cyber crime. Threat actors, including APT28 (a group with a suspected Russian nexus), and OceanLotus (a group with a suspected Vietnam nexus), have used OAuth phishing in recent digital espionage operations.

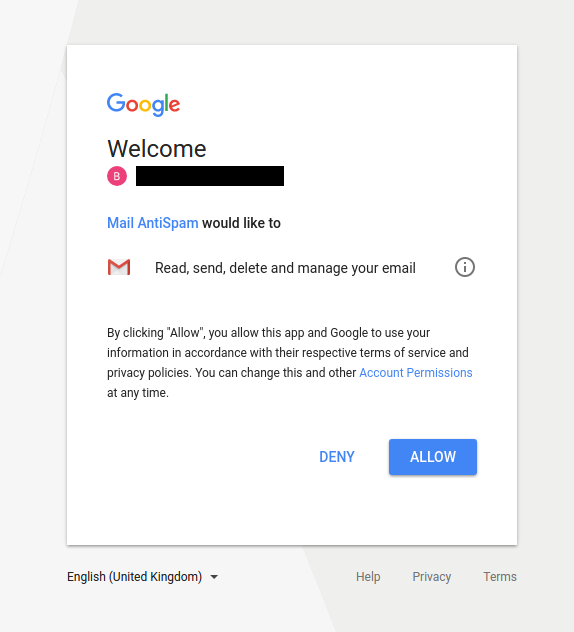

On May 8 2017, we found a malicious OAuth app hosted on the domain: mail-modular[.]space. At that time, a web request to this domain would redirect to a Google server asking for access to an OAuth application called “Mail AntiSpam”. The application requests permission to read, send, delete, and manage emails in the user’s Gmail account (see Figure 17). After successful authentication the user is redirected to mail-modular[.]space://auth2callback.php.

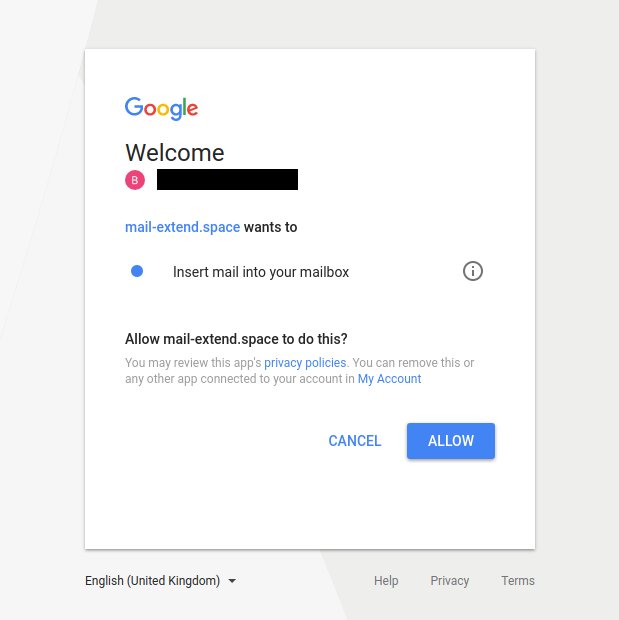

On May 18, we found another OAuth app called “My Drvie files” [sic] hosted on mail-extend[.]space. This application only requested access rights to insert emails in the account’s inbox (see Figure 18).

Table 3 summarizes the two malicious Google OAuth apps.

| App ID | App Name | Email address | First seen |

|---|---|---|---|

374922381928-objdv07ir15t9n2sfhqvcg0abub6ahog.apps.googleusercontent.com |

Mail AntiSpam | mailantispamcenter[@]gmail.com | May 8 2017 |

894999984303-l97vu17uvco2h982uk4tuh4106i2qrst.apps.googleusercontent.com |

My Drvie Files | myfiledrives[@]gmail.com | May 18 2017 |

Table 3: Summary of malicious OAuth Applications

Malware connected to Infrastructure

In addition to the phishing activity, we identified a malware sample on VirusTotal that used one of the domains in the operation’s infrastructure (phpinfo[.]pw) as a command and control server. The domain was registered with the same WHOIS information used to register other domains in this operation and resolved to 104.207.132[.]165 between March 2016 and March 2017. We did not find any use of this malware in the wild. The malware appears to be custom developed, but of low technical sophistication. It is designed to find files with specific keywords in their name or path, and send them to the C2 server. A full analysis of the sample is provided in Appendix A.

Part 2: Targeting

This section describes the targets and tactics of the operation including tracking phishing campaigns targeting Tibetan groups and analysis of decoy documents with targeting themes beyond the Tibetan community.

Targeting the Tibetan Community

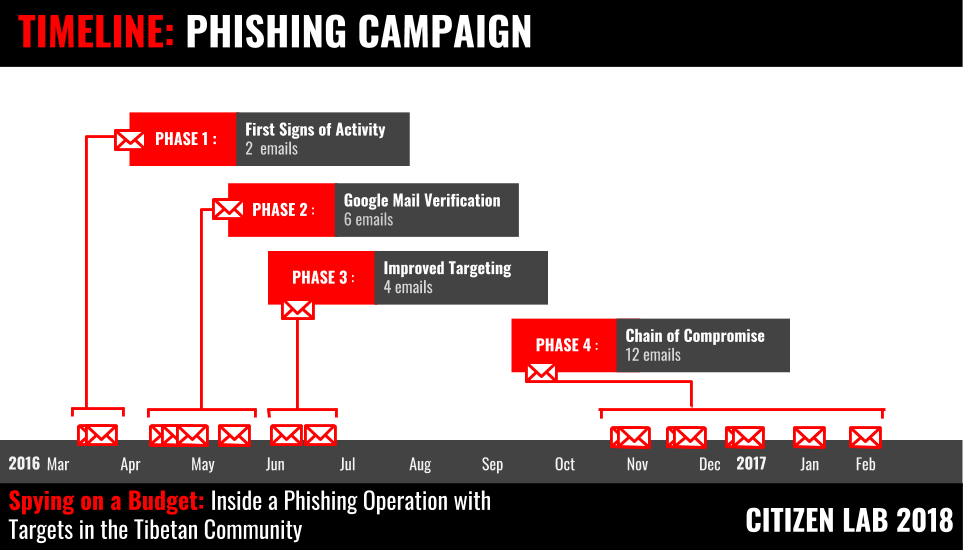

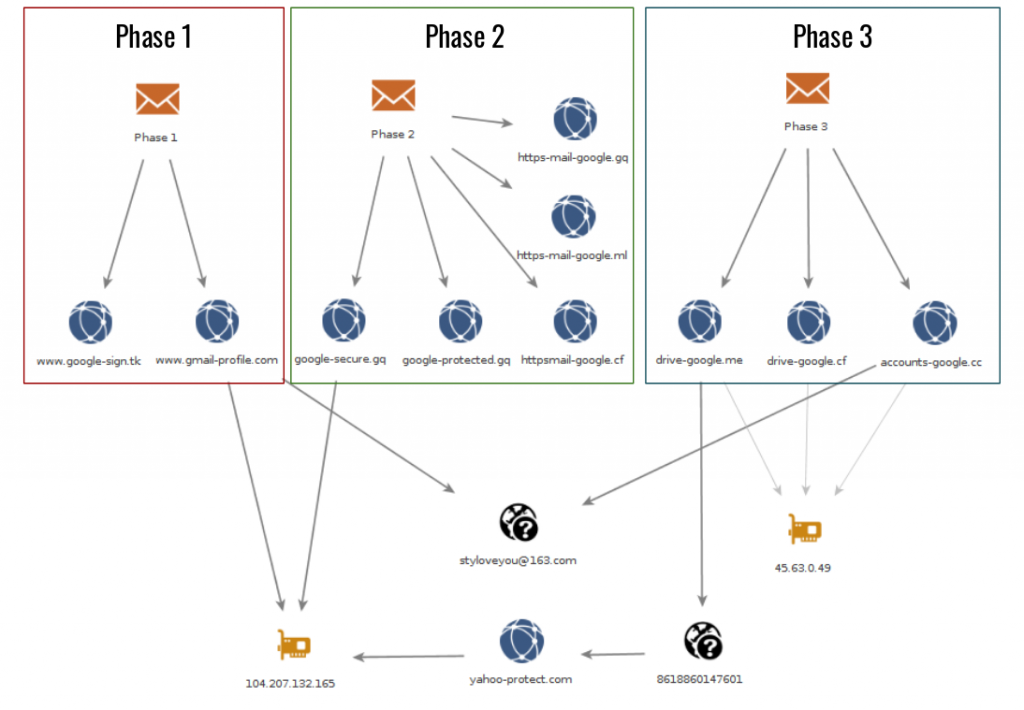

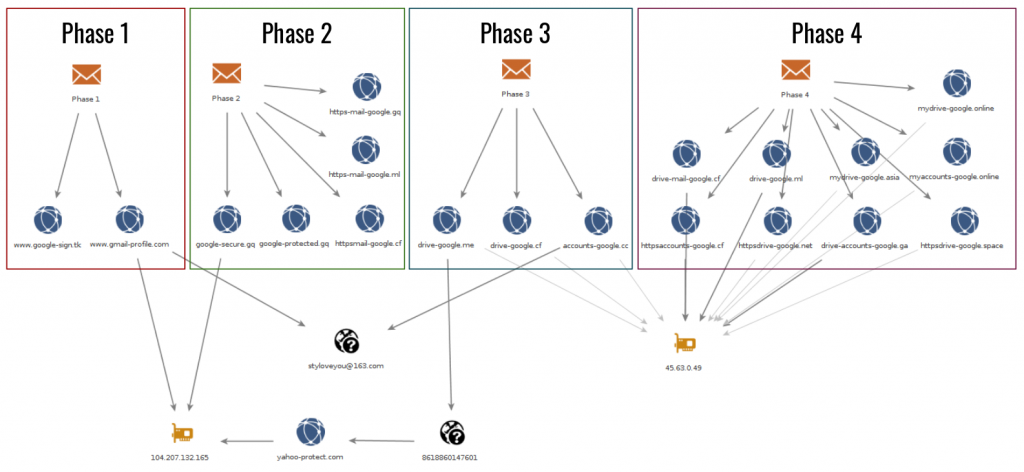

Between March 21, 2016 to February 21, 2017 we collected 24 phishing emails sent to Tibetan human rights groups and email addresses associated with the CTA. We cluster these emails into four distinct phases based on time, social engineering tactics, and infrastructure. Figure 19 shows a timeline of the phishing operation divided into the four phases. We detail each phase in the sections below.

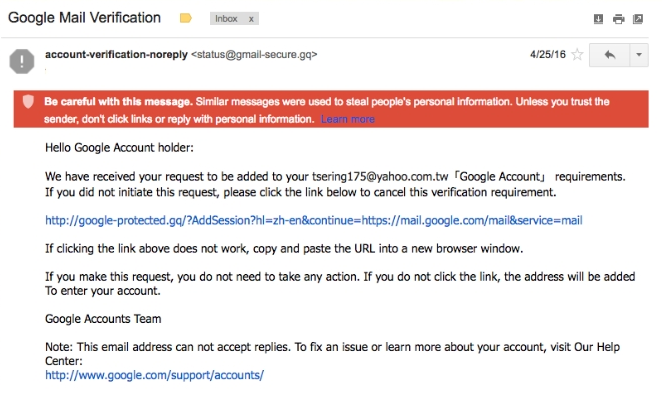

Phase 1: First signs of activity

In the first phase, on March 21 and March 29 2016, two phishing emails were sent to a Tibetan human rights group. The phishing pages were not live during the period that we collected the emails. However, we retrieved decoy content that show these phishing attempts follow the general social engineering we see throughout the operation.

Social Engineering

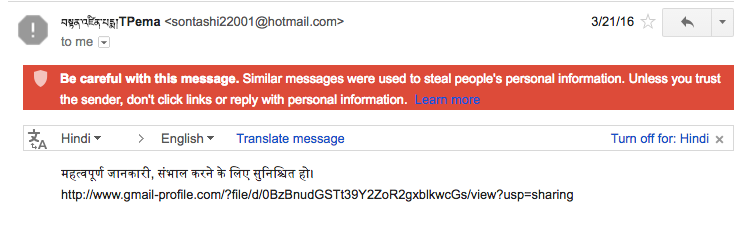

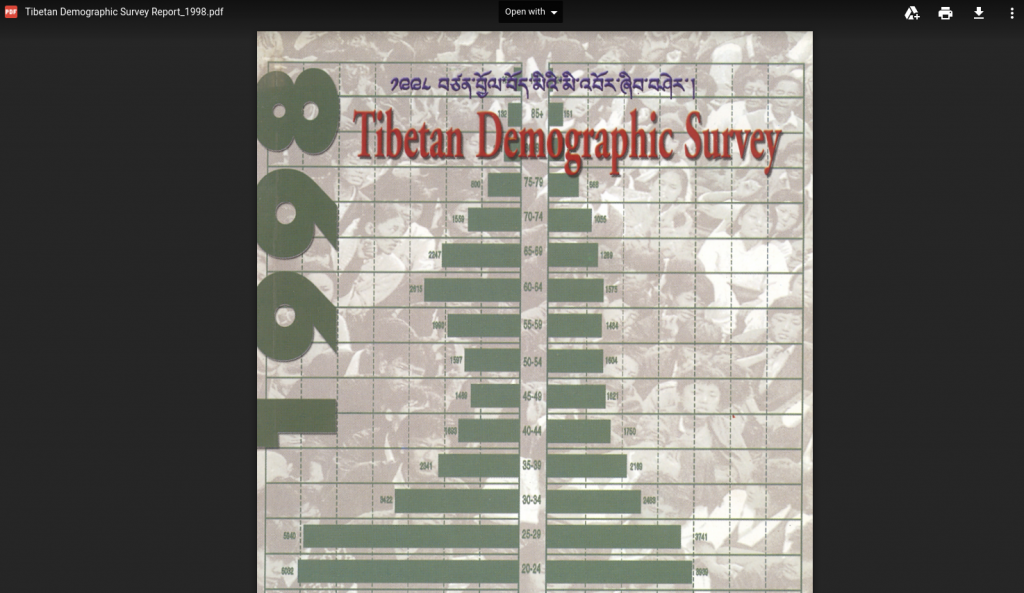

On March 21 2016, a staff member of the group received a phishing email appearing to be from an individual with a Tibetan name “Tenzin Pema (བསྟན་འཛིན་པདྨ།)” with the subject “Tibetan Demographic Survey Report_1998”, a message in Hindi expressing “Important information , Make sure to care!”, and a link to a domain made to resemble Gmail (See Figure 20).

The 1998 Tibetan Demographic Survey Report was the first census released on the Tibetan community in exile, and was updated in 2009. The decoy document is a copy of the report (See Figure 21). The reference to an outdated document and use of Hindi makes for unconvincing social engineering for the targeted groups.

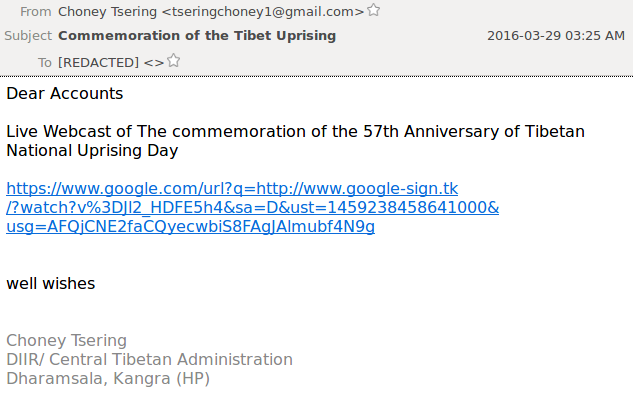

On March 29, the same staff member received an email that appeared to be sent from a representative of the CTA that shared a Google lookalike link to a webcast of an event commemorating the anniversary of Tibetan Uprising Day (See Figure 22).

The phishing page this link would lead to was not active when we received the email, but the decoy content was a video of the event the email described hosted on YouTube (See Figure 23).

Infrastructure

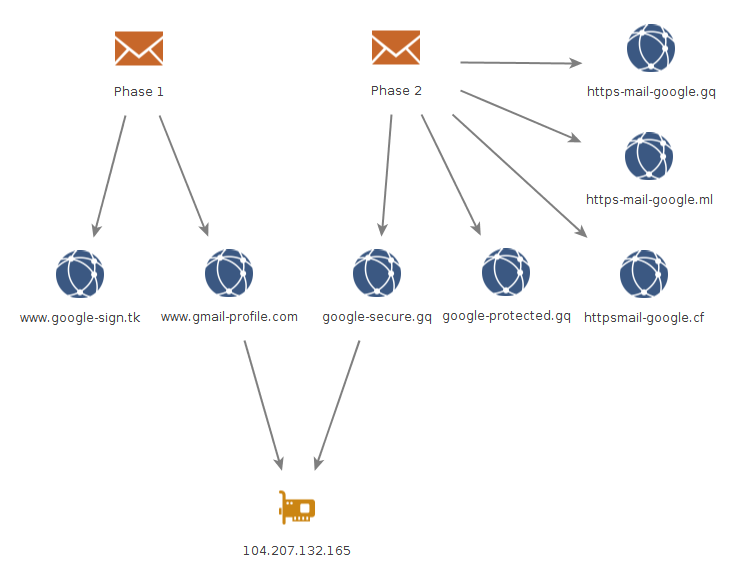

The domain gmail-profile[.]com resolved to the first server used in the operation: 104.207.132[.]165. No domain resolution information was available for the other fake domain (www.google-sign[.]tk)

The whois information for gmail-profile[.]com is as follows:

Phase 2: Google Mail Verification

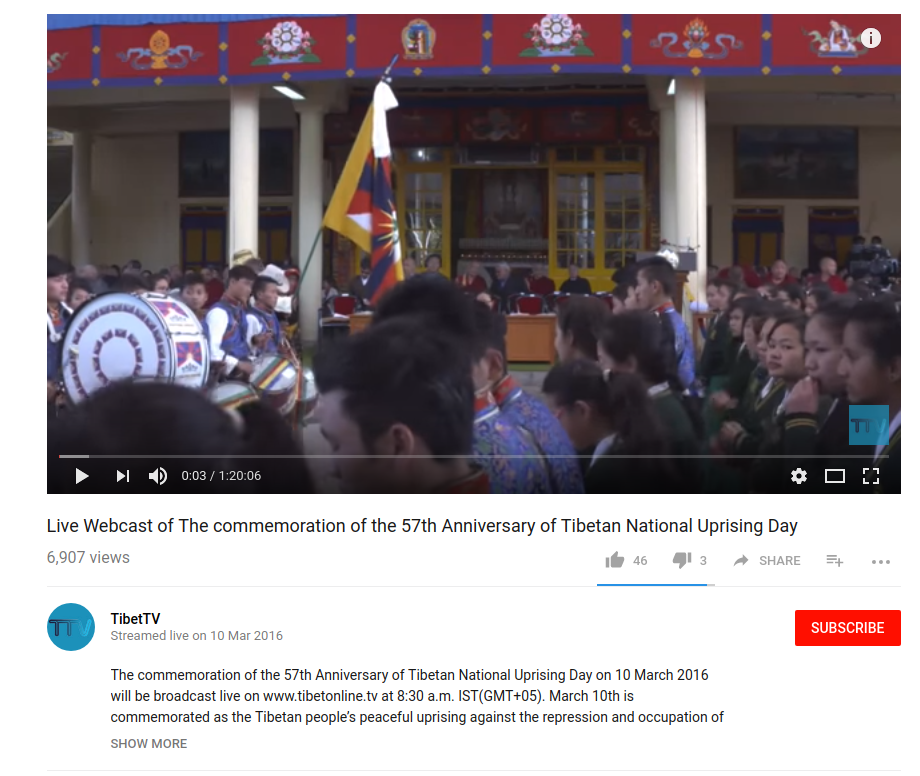

We collected six phishing emails sent to two Tibetan human rights groups between April 21 and May 31, 2016, which all used a common template made to appear to be a security notification from Google.

Social Engineering

Each email swaps out the email address referred to in the line: “We have received your request to be added to your [EMAIL]「Google Account」 requirements”. In each attempt the email referenced was a Yahoo account that did not match the recipients’ emails, which were all Gmail accounts (see Figure 24).

In total five Yahoo emails were referenced. The majority of these emails used Tibetan names or references to Tibetan groups. However, some were not related to the Tibetan community such as “chinesepen@yahoo.com” which may be a reference to the Independent Chinese PEN Center which is a member of International PEN, a global association of writers and artists concerned with freedom of expression and human rights. The mismatch between the referenced Yahoo email addresses and the template designed for Google credential phishing may be a mistake made by the operators suggesting they are also targeting Yahoo accounts in other campaigns that may include groups outside of the Tibetan community.

Infrastructure

The phishing domains used were made to look like Google services, but none of the phishing pages were live at the time of collection.

Passive DNS records were not available for the majority of the domains with the exception of google-secure[.]gq which resolved to 104.207.132[.]165, the same IP that the domain used in Phase 1 resolved to (see Figure 25).

Phase 3: Improved Targeting

In Phase 3, four emails were sent to the two Tibetan groups between June 13 and July 15, 2016.

Social Engineering

The social engineering used in the phishing emails in this phase return to Tibetan themes and are made to appear to come from Tibetan groups or individuals and included what appeared to be links to image files (see Figure 26).

If a target entered credentials into the linked phishing page an image file hosted on Google Drive would be presented such as the photograph of Mount Everest shown in Figure 27.

Infrastructure

The domains used in Phase 3 were hosted on the second server used in the operation (see Table 4).

| Domain | Passive DNS |

|---|---|

| drive-google[.]me | 45.63.0[.]49 |

| drive-google[.]cf | 45.63.0[.]49 |

| accounts-google[.]cc | 45.63.0[.]49 |

Table 4: Summary of domains used in Phase 3.

Domain registration information provides connections between this infrastructure and the other phases. The email (styloveyou[@]163.com) was used to register domains in Phase 1 and a domain from Phase 3 (accounts-google[.]cc).

Another Yahoo lookalike domain (yahoo-protect[.]com) was registered with the same phone number (8618860147601) which registered drive-google[.]me and which pointed to the IP address used in phase 1 (104.207.132[.]165). Figure 28 shows infrastructure connections between Phases 1, 2, and 3.

Phase 4: Chain of Compromise

The fourth phase consisted of 12 emails sent between Nov 1, 2016 and February 21, 2017 with the majority of emails sent in late December. During this phase we see wider targeting in the Tibetan community, including the CTA, and compromised accounts sending phishing emails to large lists of recipients, which were likely harvested from the contact list of the account.

Social Engineering

The social engineering used in this phase included messages with relevant content and senders that appeared legitimate (and in some cases were sent from compromised accounts). We suspect that the improvements to targeting in this phase were due to the operators leveraging information collected from compromised accounts.

On December 30, 2016, a phishing email was sent from a @tibet.net email address, (tibet.net is a domain used by the Central Tibetan Administration for its official website and email services), to a list of 241 recipients. Analysis of the email headers show the email sender was legitimate suggesting that the account had been compromised.

The email purported to send a picture which linked to a fake Google domain:

We observed two other phishing emails sent from a Gmail address included in the recipient list four hours before and 15 hours after the message from the @tibet.net address. These emails also purported to contain an image which linked to a fake Google domain. We suspect this address was also compromised. This series of emails shows how the operators harvest contacts and other information from compromised accounts and feed it into further targeting.

Infrastructure

Table 5 lists the nine domains that were used during Phase 4, which were all hosted on the same server as Phase 3.

| Domain | Passive DNS |

|---|---|

| httpsaccounts-google.cf | 45.63.0[.]49 |

| drive-accounts-google.ga | 45.63.0[.]49 |

| drive-google.ml | 45.63.0[.]49 |

| drive-mail-google.cf | 45.63.0[.]49 |

| myaccounts-google.online | 45.63.0[.]49 |

| mydrive-google.online | 45.63.0[.]49 |

| mydrive-google.asia | 45.63.0[.]49 |

| httpsdrive-google.net | 45.63.0[.]49 |

| httpsdrive-google.space | 45.63.0[.]49 |

Table 5: Summary of domains used in Phase 4

Figure 29 shows the infrastructure connections between the four phases.

Targeting Beyond Tibetan Groups

The phishing emails we collected from Tibetan groups provide our best visibility into the social engineering and targeting tactics used in the operation, but represent only a small piece of the overall activity. In addition to the phishing emails targeting Tibetan groups we found decoy documents with a range of themes suggesting other potential targeting.

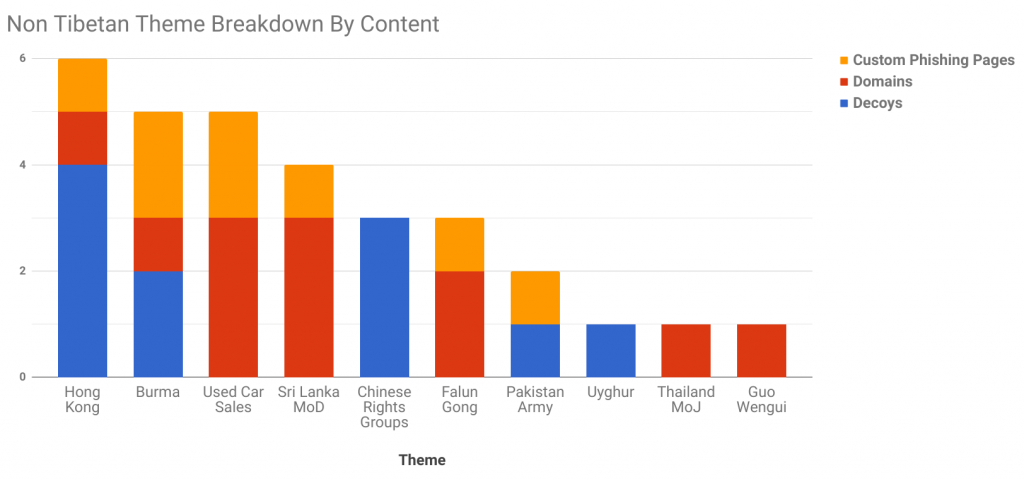

Beginning on February 23, 2017 we began to systematically download decoy documents served from the phishing pages, collecting a total of 58 files. Tibetan politics and culture was the most consistent theme across the files accounting for 41 decoy documents, but we also found reference to ten other themes based on the content of documents, phishing pages, and domain names.

These other themes included social movements and groups in China such as ethnic minorities (Uyghurs), Falun Gong-related media (Epoch Times), and a group working on rights issues in China. Themes also included reference to South Asian and Southeast Asian governmental agencies such as the Pakistan Army, the Sri Lanka Ministry of Defence, and the Thailand Ministry of Justice. Other decoy content referenced Hong Kong-based companies and a mail provider operated by a Burmese Internet Service Provider. The operators also registered a domain that referenced Guo Wengui, a Chinese billionaire who gained notoriety after voicing allegations that high ranking officials in the Communist Party of China are engaged in corruption (however, we never saw this domain used for any activities and it never resolved to an IP address). We also found a phishing page mimicking Chinese used car websites, which may be evidence of the operators using the infrastructure for general cyber crime activities.

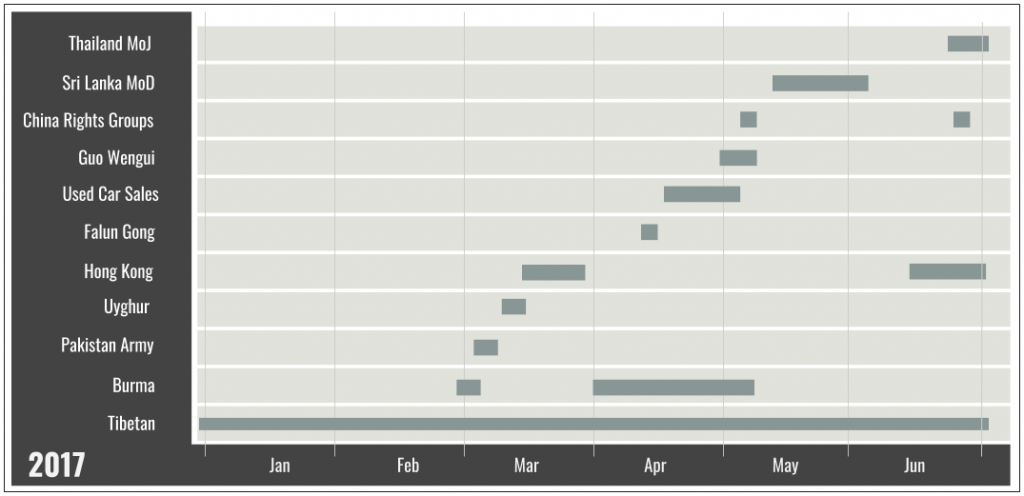

Figure 30 shows the breakdown of non-Tibetan themes by the type of content used. Appendix B provides detailed examples of each targeting theme.

Figure 31 provides a timeline of themes based on when we found the first evidence of a decoy document, phishing page, or domain, and the general period of activity for each theme.

Based on the content and metadata of files we determined if the document was publicly available online or potentially a private file. We grouped the files into three categories — private, public and unknown — based on our estimation of their publicity. Private files included grant contracts and meeting minutes for a human rights group working on issues in China and legal documents and policy materials from the Central Tibetan Administration. We suspect these documents were collected from accounts compromised during the operation. Table 6 shows the distribution of file types and themes.

| Theme | Type | Number of Documents |

|---|---|---|

| Tibet | PRIVATE | 11 |

| PUBLIC | 16 | |

| UNKNOWN | 14 | |

| Hong Kong | PUBLIC | 1 |

| UNKNOWN | 3 | |

| China Rights Group | PRIVATE | 3 |

| Burma | PUBLIC | 2 |

| Pakistan | PUBLIC | 1 |

| Uyghur | PUBLIC | 1 |

| Misc | PUBLIC | 2 |

| UNKNOWN | 4 |

Table 6: Decoy documents organized by type and theme.

The diversity of themes suggests the operators were interested in a wider group of targets outside of the Tibetan community. A commonality across these themes is that they are all of political interest to the government of China. Social movements, religious groups, and ethnic minorities are sensitive political issues in China. Uyghurs, Falun Gong supporters, and Tibetan groups are well documented targets of digital espionage operations that are often suspected to be carried out by operators directly sponsored or tacitly supported by Chinese government agents. Government agencies in South Asia and South-East Asia are also within the geopolitical interests of China and are frequently targeted by digital espionage. Despite these commonalities, it is unclear how the operators selected targets. Nor is it clear if the operators had a specific sponsor and/or who was the ultimate consumer of data collected.

Part 3: Discussion and Conclusion

This section discusses the implications of our analysis.

This report shows that effective digital spying operations do not require deep pockets or sophisticated technical skills to be effective at accessing sensitive information. While digital threats against civil society range widely in sophistication and technique it is evident that there is a gap between the state of the threat, and the ability of civil society groups to protect themselves. Efforts undertaken within civil society, like behavioural change programs and awareness efforts, and steps taken by companies can all contribute to closing the gap. Unfortunately, some of the most important security tools provided by companies are not being effectively promoted and mainstreamed to their user bases.

Low Entry Costs for Digital Spying

The operators in this case demonstrated only basic technical skills and committed a number of errors and operational security mistakes that made it easier to track their activities. This profile suggests the operator may be a low level contractor servicing multiple clients or a single client with multiple targeting interests. The sloppiness on the part of the operators may also show they are working in an environment without any effective deterrent to their activities, and possibly even some kind of informal high-level support. Finally, the targeting of second hand selling car websites also suggests that the operators may be engaged in conventional cyber crime.

The report adds to previous investigations that have repeatedly shown that many threat actors, including those with access to more sophisticated capabilities, persist in using phishing and other forms of basic social engineering to target civil society. Previous work has tracked phishing campaigns targeting Egyptian civil society, journalists in Latin America, Syrian opposition groups, Iranian pro-democracy organizations, and many others. The relatively low cost, scalability, and adaptability of phishing make it an attractive option that we expect will continue to be an active threat for civil society.

Behaviour change is slow, but attackers adapt quickly

For the Tibetan community in particular, this operation is another example of a shift from targeted malware to phishing operations. Previous research has shown that in the past the most common digital espionage threat used against the Tibetan community was document-based malware sent as email attachments. Some Tibetan groups reacted to this threat by promoting the use of cloud platforms to share documents, such as Google Drive and Dropbox, as an alternative to email attachments. While this behavioural change is a potentially effective mitigation against malware sent as attachments, shifting practices in a community can take a long time to achieve. Operators on the other hand can adapt on a much shorter timescale. For example, as Tibetan groups started to avoid attachments and use cloud alternatives we saw operators pivot to sending malware through Google Drive. We simultaneously observeda drop in malware campaigns against Tibetan groups and a rise in phishing operations.

Community security education efforts and behaviour change programs can lead to the adoption of more secure behaviours and are an important step in mitigating these threats. However, the long timescale of these efforts, combined with often-limited feedback about their success, is little match for the rapid iteration available to operators. For example, we observed the operators in this case experimenting with OAuth apps to steal account credentials. It is unclear who the operators targeted with the malicious OAuth apps, but their use could be a means to bypass users with two factor authentication on their Google accounts. The abuse of OAuth shows that operators will continue to adapt and innovate when necessary and apply just enough technical sophistication and tricks to achieve their objectives.

Raising the Cost of Digital Spying and Protecting Users

Efforts to increase security awareness are important, despite their limitations, but are not the only tools available to mitigate the harm caused by phishing. Much of the threat posed by this operation could have been blunted by security features like two factor authentication, which are available on widely-used consumer platforms like Gmail. Unfortunately, user adoption rates for two factor authentication are extremely low, although many companies avoid providing public figures that could illustrate just how dire the situation is. Indeed, even users who have experienced a breach are unlikely to enable these security features (roughly 3.1% according to a recent study). In other words, security features are unlikely to be enabled, even when the stakes are very high. These low rates likely reflect a range of user variables, such as awareness, motivation, and technical literacy, as well as the difficulty and time required to follow the multi-step process to enable them.

The low adoption rates for two factor authentication raises the question of what other steps companies can take to make security features mainstream for all users. These steps might include enabling a form of two factor authentication as default-on when a new account is created, or developing better behavioural nudges to increase adoption rates. Unfortunately, companies may be avoiding these efforts out of concerns of losing users by adding friction to account use and recovery, or incurring additional costs for customer service.

Civil society groups, like many organizations and businesses, rely on popular consumer platforms to disseminate information, gain public visibility, and communicate. Some widely-used platforms have clearly taken notice of the unique threats faced by these populations and added security options tailored to them, such as an “advanced security program” (Google) which implement multiple U2F security tokens, and other account security features.

While these programs are interesting (and too new to properly evaluate), our experience suggests that the same behavioural hurdles will apply to them, and that adoption rates will not match the size of the user population that is likely to be targeted. There is a clear and urgent imperative to shift users to a more secure authentication process. This change can only happen when companies develop a clear intention to fix this problem, and commit to a goal of achieving a specific adoption rate for these security features in a limited timeframe.

Addressing this problem goes beyond helping civil society. A combination of security education and wider adoption of security features like two factor authentication can help raise the low bar by making digital spying more expensive and immediately benefit high risk users. Paying attention to the security challenges that plague civil society on popular platforms can in turn confer greater security to the wider user population.

Footnotes

[1] While techniques for phishing two factor authentication are in use, they appear to require more resources and effort.

[2] Umaylam is the Tibetan term for “The Middle Way Approach for Genuine Autonomy for the Tibetan People”, which is an official policy of His Holiness the Dalai Lama and the CTA that seeks genuine autonomy (rather than complete independence) from the People’s Republic of China.

[3] These rough costs estimates are based on our analysis of infrastructure and services used by the operators. The estimate considers the lowest cost based on the services used.

The estimate is the based on the following calculations:

10 USD / month for servers x 19 months = 190 USD

10 USD / year for common domains x 79 domains = 790 USD

2 USD / year for .space domains x 44 domains = 88 USD

Server Estimate (190 USD): The operators used three servers between the period of January 2016 to July 2017. Only one server was used at a time. The most cost effective solution would be to use Virtual Private Servers, which can be purchased for approximately 10 USD per month. A more expensive option would be to purchase dedicated servers (for example, Choopa, one of the providers the operators sells dedicated servers for 70 USD per month).

Domain Registration Estimate (918 USD): The primary infrastructure related expense was from registering 172 domains, mainly from GoDaddy and Hong Kong DNS. The operators used many TLDs having free domains for the first year (like .gq or .ga), likely to reduce the cost (49 of these domains were free). They also used TLDs with lower annual prices such as .space which can be registered for 2 USD per year on GoDaddy. Common top level domains cost an average of 10 USD to register on GoDaddy.

HTTPS Certificate Estimate (Free): The operators used 43 different HTTPS certificates for domains used in the operation. Four of these certificates were created using Let’s Encrypt, a free, automated, and open certificate authority. Thirty-nine certificates were signed by Comodo. Our analysis found that for the these Comodo certificates, the operators leveraged a bug on a platform from hosting provider UK2, which allowed free certificate registration.

[4] This analysis only includes domains that have available registration dates. Certain TLDs such as .cf do not include this information in WHOIS data.

Acknowledgements

Authors in alphabetical order.

Special thanks to Lobsang Gyatso, Tibet Action Institute, and the participating Tibetan organizations. We are grateful to Ron Deibert for guidance and supervision, to Adam Senft and Miles Kenyon for copy editing, and to TNG.

Figures 5 and 6 include icons created by Genius Icons (URL), Ralf Schmitzer (server), Creative Outlet (clock), Xinh Studio (clock) Pro Symbols (certificate), Andrew Doane (money stack), Milky Digital Innovation (target) licensed under CC BY 3.0 from the Noun Project.

Indicators of Compromise

Indicators of compromise are available on GitHub in multiple formats.

Appendix A: Malware Analysis

Summary

The sample is a self-extracting program, which drops both a legitimate Windows Media Player binary (e04ffd291915cd0db9c3ae8743f68c8c) and malicious file called playlib.exe (0963bee29e797ea7481be5f18f354029).

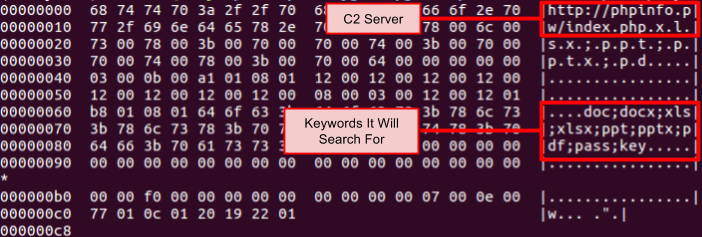

The malicious file (playlib.exe) was developed in C++ using the Qt library packaged using Enigma Virtual Box to be portable. Its main objective is to search the infected hard drive for files with specific keywords to identify Microsoft Office documents, passwords and keyfiles and send these files to the C2 server.

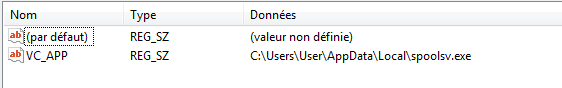

Installation and persistence

When running for the first time, the program copies itself in an AppData folder (C:\Users\[USERNAME]\AppData\Local\ on windows 7) as spoolsv.exe and creates a Run key VC_APP in HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\run. It then reads the configuration and creates an ini file upload_Log.ini in the same folder including the configuration in a section called section1.

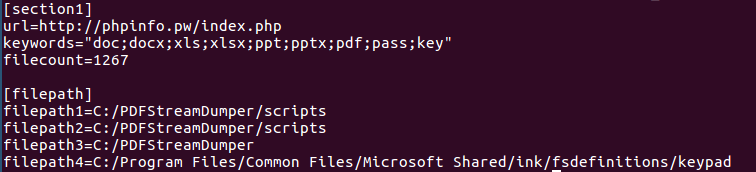

Search for files

When the program is launched, it first checks if the ini file exists and if it contains a list of files (checking the filecount parameter). If the filecount parameter is 0, it then starts enumerating files on the disk and write name, path and last modification date of every file containing one of the key words in its path.

upload_Log.ini (first 10 lines)Once the enumeration is done, the program reads every file listed in the .ini file and sends it to the C2 server with its filename. On a second execution, the malware confirms that the enumeration was already done by checking the .ini file. It then checks the last modification time of every file listed, and sends any files that were modified since the previous execution.

Configuration

The configuration file is stored in the 200 extra-bytes at the end of the PE file (C2 address at END-200 and the list of key words at END-100).

This configuration includes keyword targeting files made in Microsoft Office, passwords, and key files with the following file extensions:

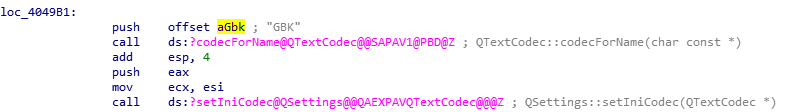

GBK codes

The program uses GBK Qt codec as encoding type when reading or writing files. The GBK codec is for Chinese language.Chinese language.

Appendix B: Targeting Theme Examples

Tibet

| Timeline | March 2016 to July 2017 |

|---|---|

| Number of decoy documents | 41 |

| Number of domains | 5 |

| Number of customized phishing pages | 3 |

Tibetan themed domains and decoy content was the most consistent theme across the operation including domains that mimicked Tibetan organizations such as the official website of His Holiness the Dalai Lama and the Central Tibetan Administration website. The operators also designed fake login pages to spoof mail services on the Dalai Lama’s website.

| Domain | Registration Date | Registrant | Registrar |

|---|---|---|---|

webmail-dalailama[.]com |

2017-04-06 | deepcliff[@]sina.com | Go Daddy |

webmail.dalailama[.]space |

2017-04-02 | deepcliff[@]sina.com | Go Daddy |

t1bet[.]net |

2016-04-03 | styloveyou[@]163.com | HK DNS |

tibet-office[.]net |

2016-11-22 | leungguodong[@]outlook.com | Go Daddy |

webmail-dalailama[.]space |

2017-05-27 | deepcliff[@]sina.com | Go Daddy |

We collected a total of 41 Tibetan related documents used as decoy content and estimate that at least 11 of them are private documents.

China Rights Group

| Timeline | May and June 2017 |

|---|---|

| Number of decoy documents | 3 |

| Number of domains | 0 |

| Number of phishing pages | 0 |

In May and June 2017, we identified three Google Drive documents used as decoys for generic phishing domains and Google lookalike domains (e.g., mail-gooog1e[.]info). The documents appear to be files related to an NGO working on human rights issues in China including grant documentation and meeting minutes. The nature of the documents indicate they are likely private files.

Uyghur

| Timeline | March 2017 |

|---|---|

| Number of decoy documents | 1 |

| Number of domains | 0 |

| Number of phishing pages | 0 |

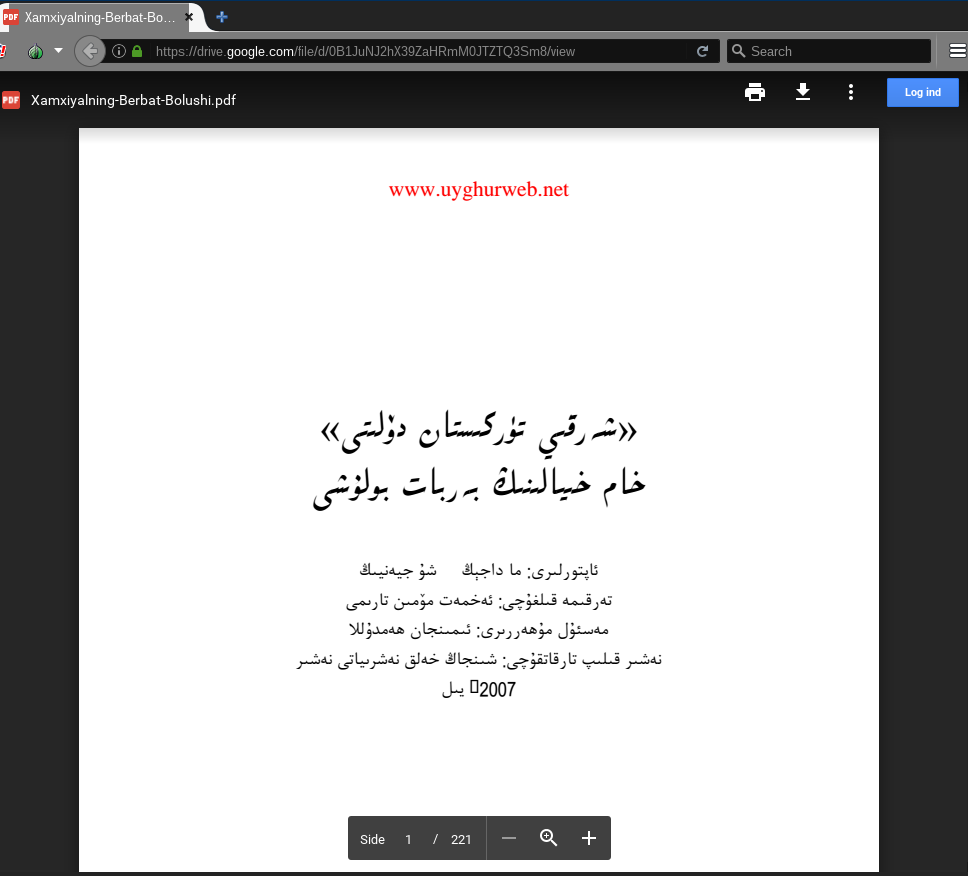

On March 10, 2017 we identified a fake Google login page on the domain drive-mail[.]info. If credentials were into the page the user would be redirected to a document in the Uyghur language on Google Drive. This document is publicly available from the World Uyghur Congress website. Google Drive metadata on the document shows that it was uploaded on March 8, two days before it was used as a decoy.

Epoch Times

| Timeline | April 2017 |

|---|---|

| Number of decoy documents | 0 |

| Number of domains | 2 |

| Number of phishing pages | 1 |

In April 2017, we identified two domains mimicking Epoch Times, a multilingual media organization started by Chinese-American Falun Gong supporters. The domain was registered with the same email addresses that was seen in other domains in this campaign.

| Domain | Registration Date | Registrant | Registrar |

|---|---|---|---|

mail-epochtimes[.]space |

2017-04-11 | deepcliff[@]sina.com | GoDaddy |

epochtimes[.]space |

2017-04-19 | evalliang[@]163.com | GoDaddy |

We identified a phishing page on the domain mail-epochtimes[.]space (hosted on 115.126.39[.]107 at that time), which is a copy of the Epoch Time webmail login page.

Guo Wengui

| Timeline | May 2017 |

|---|---|

| Number of decoy documents | 0 |

| Number of domains | 1 |

| Number of phishing pages | 0 |

Guo Wengui is a Chinese billionaire who gained notoriety after voicing allegations that high ranking officials in the Communist Party of China are engaged in corruption. Guo has been seeking asylum in the US following a request from China to Interpol to issue a global warrant for his arrest

On May 2 2017, the operators registered a domain that referenced Guo’s name. We have not seen any resolution for this domain, or any other utilization of it.

| Domain | Registration Date | Registrant | Registrar |

|---|---|---|---|

wengiguowengui[.]space |

2017-05-02 | deepcliff[@]sina.com | Go Daddy |

Hong Kong

| Timeline | June 2016, March to July 2017 |

|---|---|

| Number of decoy documents | 4 |

| Number of domains | 1 |

| Number of phishing pages | 1 |

Between March and June 2017, we identified four decoy images hosted on Google Drive that included pictures of Hong Kong companies, an image of text in Chinese referencing political issues in Hong Kong, and an image of a running trail in the city.

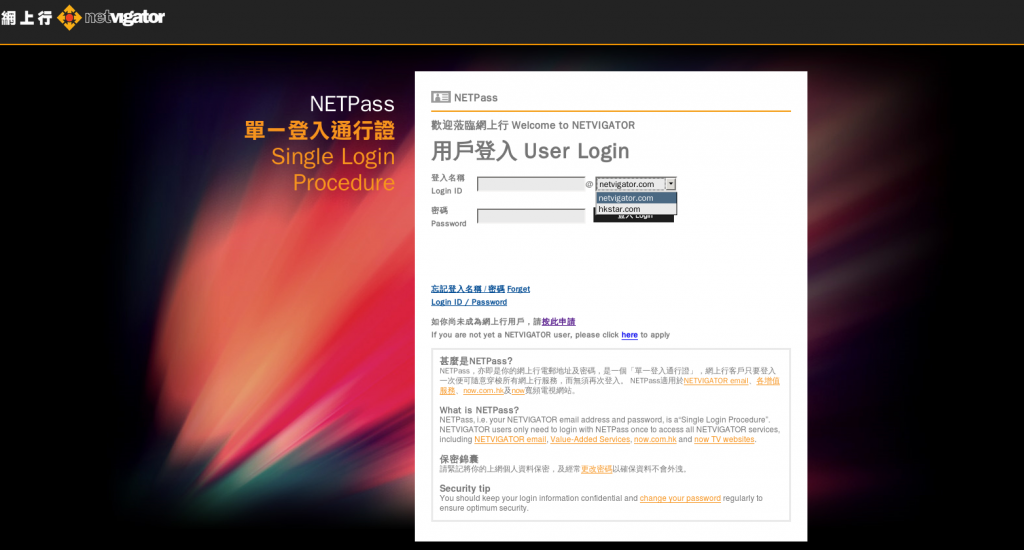

On July 1 2017, only a few days before the last day of activity in the operation we observed a domain and phishing page designed to mimic email services provided by Netvigator is the largest residential Internet service provider in Hong Kong.

| Domain | Registration Date | Registrant | Registrar |

|---|---|---|---|

email-netvigator[.]info |

June 27 2017 | deepcliff[@]yahoo.com |

Sri Lanka Ministry of Defense

| Timeline | May and June 2017 |

|---|---|

| Number of decoy documents | 0 |

| Number of domains | 3 |

| Number of phishing pages | 1 |

In June 2017, we identified several domains mimicking the Sri Lanka Ministry of Defense webmail subdomain (mail.defence.lk).

| Domain | Registration Date | Registrant | Registrar |

|---|---|---|---|

| mail-defense[.]space | May 13 2017 | deepcliff[@]sina.com | Go Daddy |

mail-defend[.]space |

May 31 2017 | deepcliff[@]sina.com | Go Daddy |

mail-defense[.]tk |

Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

In June 2017, a fake webmail login was installed on on mail-defense[.]tk that copied the legitimate login page. If credentials were entered into this page users were redirected to a file hosted on Google Drive. This file was no longer available when we found the login page.

Pakistan

| Timeline | March 2017 |

|---|---|

| Number of decoy documents | 1 |

| Number of domains | 0 |

| Number of phishing pages | 1 |

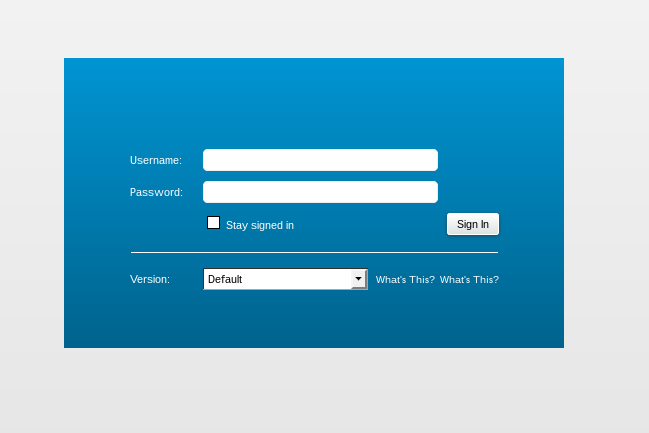

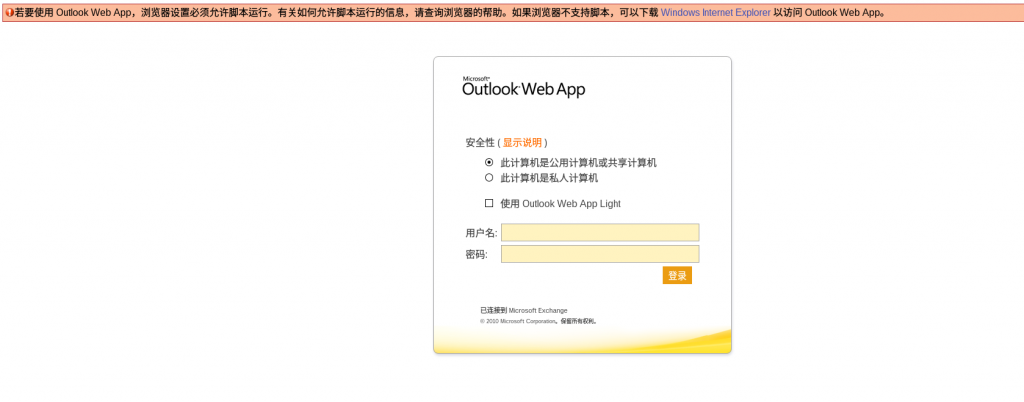

In March 2017, we found a fake Outlook login page hosted on the domain: login-live[.]us. This page was copied from the website of the Punjab government in Pakistan (https://mail.punjab.gov.pk/owa).

On March 21, if credentials were entered into the fake login page the user would be redirected to the webmail page for the Government of Punjab in Pakistan (http://mail.punjab.gov.pk/ ). On March 22, if credentials were entered the user would be redirected to decoy content on Google that showed an image from the Pakistani Army that is available on thePakistani government website.

Burma

| Timeline | February, April and May 2017 |

|---|---|

| Number of decoy documents | 2 |

| Number of domains | 1 |

| Number of phishing pages | 2 |

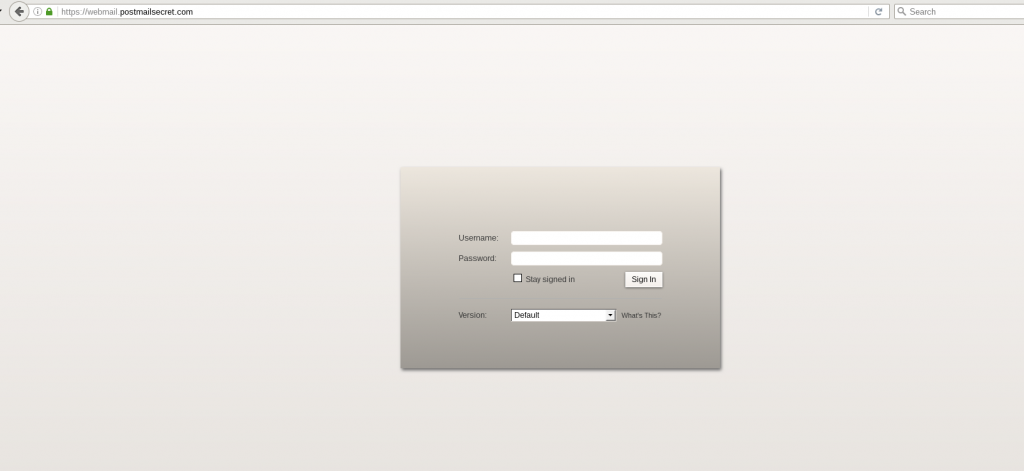

We first identified Burma-related pages in February 2017, the domain webmail.postmailsecret[.]com hosted a fake Zimbra login that was a copy of the Myanmar Post and Telecommunications (MPT) webmail. MPT is a major state owned telecommunications company in Burma.

webmail.postmailsecret[.]com (Feb 2017).When we tested it however, we found that submitting credentials to this form redirected us to a Tibetan related decoy document. In late April, we found Burma-related decoy documents, redirecting from a fake Google login page hosted on the domain: www.mail-attachment-usercontent[.]space. This picture is a photo of hot-air balloons over Bagan that is widely available online.

In May we identified a domain mimicking the webmail of MPT, but did not observe any utilization of it.

| Domain | Registration Date | Registrant | Registrar |

|---|---|---|---|

webmail-mpt[.]space |

2017-04-19 | evalliang[@]163.com | Go Daddy |

Ministry of Justice of Thailand

| Timeline | June 2017 |

|---|---|

| Number of decoy documents | 0 |

| Number of domains | 1 |

| Number of phishing pages | 0 |

In July 2017, we identified a domain mimicking the Thailand Department of Special Investigation (DSI) website. The domain mail.dsi.go.th is the official page of DSI and is part of the Thai Ministry of Justice. We have not seen any evidence of utilization of this domain.

| Domain | Registration Date | Registrant | Registrar |

|---|---|---|---|

mail-dsi-go[.]space |

2017-06-26 | deepcliff[@]sina.com | GoDaddy |

Used Car Seller

| Timeline | April and May 2017 |

|---|---|

| Number of decoy documents | 0 |

| Number of domains | 3 |

| Number of phishing pages | 2 |

In April and May 2017, we identified several domains mimicking two popular Chinese used car selling websites: Youxinpai and Guazi.

| Domain | Registration Date | Registrant | Registrar |

|---|---|---|---|

mail-youxinpai[.]com |

2017-04-17 | deepcliff[@]sina.com | Go Daddy |

| mail-guazi[.]space | 2017-05-01 | deepcliff[@]sina.com | Go Daddy |

mail-guazi[.]com |

2017-04-19 | evalliang[@]163.com | Go Daddy |

Fake login pages were hosted on mail-youxinpai[.]com (April 2017) and mail-guazi[.]space (May 2017). In both cases, the login page redirected to the real webmail address directly. We have not seen any activity related to mail-guazi[.]com.

mail-youxinpai[.]com (April 2017).